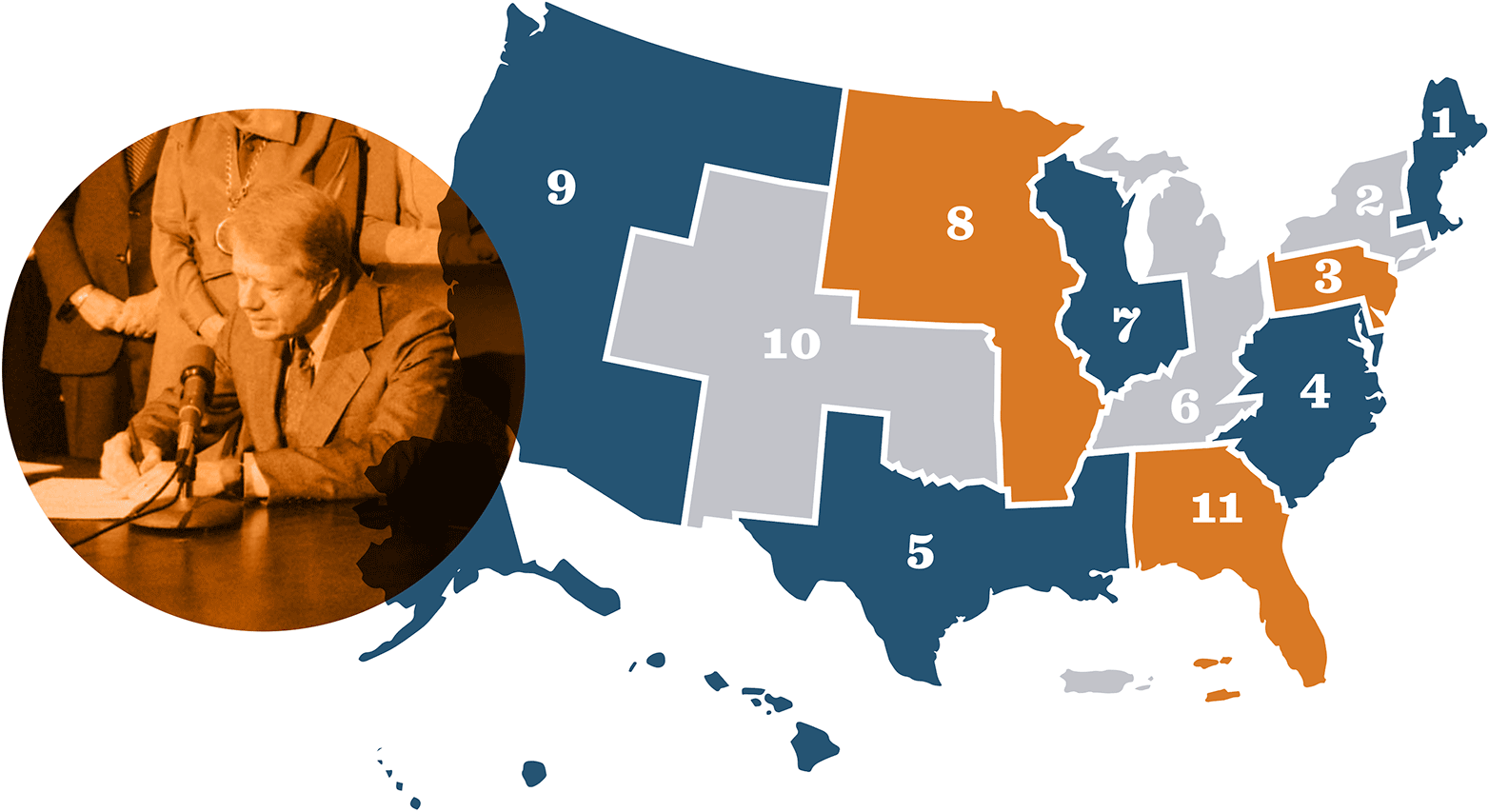

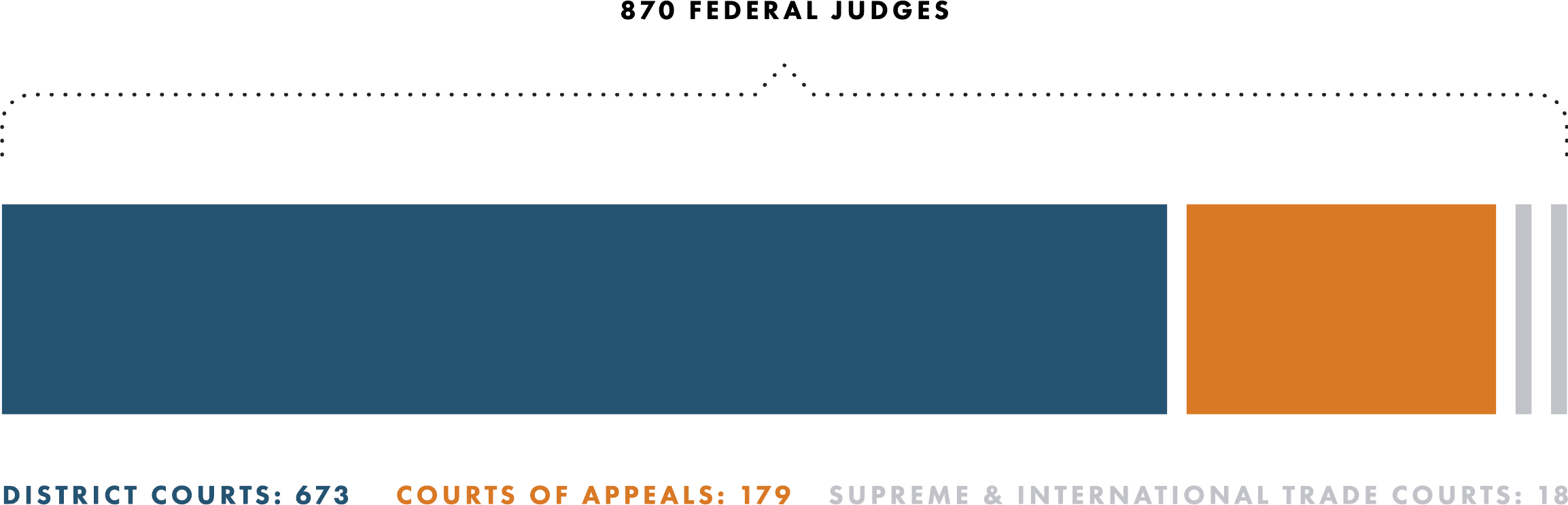

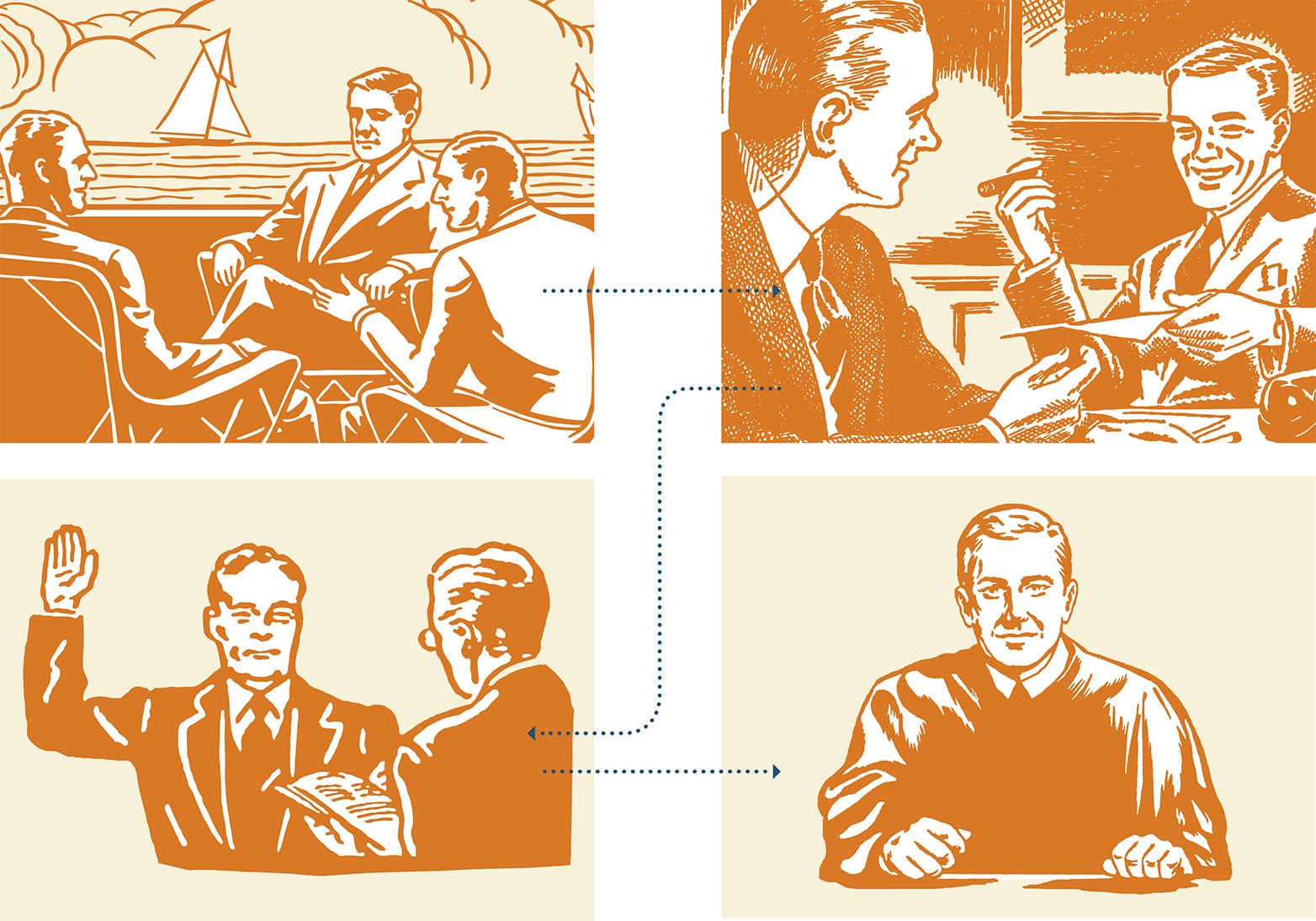

There are currently 870 lifetime federal judgeships in the United States that are authorized under Article III of the United States Constitution.1 The formal process for appointing individuals to these judgeships requires the president to nominate candidates and then requires the Senate to confirm those candidates through a majority vote.

In practice, the process for selecting judges often begins with the senators who represent the state where a district court judgeship is located. In many cases, this means that senators recommend the individuals that they would like to see appointed to the judgeships and then the president generally nominates those individuals. For circuit court judgeships, there is traditionally less deference to home-state Senators, although presidents often receive recommendations from them.

How the president ends up with judicial nominees is thus critically important for determining the shape of the federal judiciary. Yet little is known about how senators populate their lists of suggestions.

For this paper, we reached out to every Democratic senator and requested information about the process that they use to identify the individuals that they recommend for federal judgeships. Of the 45 senators who have made judicial recommendations, 37 have created a committee of people to help them do so. Nineteen of the 37 senators with such committees have publicly available information about who sits on their committee. Our research into the backgrounds of those individuals revealed that these committees are disproportionately composed of corporate lawyers and prosecutors. The remaining 18 senators with committees operate in complete secrecy.

In section one of this paper, we outline the information that we collected for this project. In section two, we make recommendations for how the process of judicial selection should work.

In short, we believe that the current Senate-based committee system should be abandoned entirely in favor of an executive commission composed of demographically-representative individuals who practice law on behalf of workers, consumers, criminal defendants, and other underdog groups in our society. Absent that, we also provide recommendations for improving the current committee system if it remains in place.