Michael Green wrote a piece at The Free Press in which he provocatively argues that the real poverty line is $140,000. There is not really much to the piece. Green just plugged a New Jersey county into Amy K. Glasmeier’s Living Wage calculator and got served a page that says that a two-earner, two-child family in that county needs to earn $136,498 to meet their “basic needs.” Glasmeier’s figures assume both children are currently in child care, use the 40th percentile rent for housing costs, and use median and average spending amounts on most of the other expenditure items. Realistically, it is an estimate of the median standard of living rather than an estimate of “basic needs,” which is why the figure is so much higher than more conventional poverty lines.

Nonetheless, Green’s piece set off a wave of secondary commentary, including pieces from Jerusalem Demsas, Scott Winship, and Matt Yglesias. Yglesias’s piece seizes on the part of Green’s piece that argues that people used to be able to live on a single income but not anymore. Here is Green:

For that time, that floor made sense. Housing was relatively cheap. A family could rent a decent apartment or buy a home on a single income. Healthcare was provided by employers and cost relatively little (Blue Cross coverage cost in the range of $10 per month). Childcare didn’t really exist as a market—mothers stayed home, family helped, or neighbors (who likely had someone home) watched each others’ kids. Cars were affordable, if prone to breakdowns. College tuition could be covered with a summer job.

Orshansky’s food-times-three formula was crude, but as a crisis threshold—a measure of “too little”—it roughly corresponded to reality. But everything changed between 1963 and 2024. Housing costs exploded. Healthcare became the largest household expense for many families. Employer coverage shrank while deductibles grew. Childcare became a market, and that market became ruinously expensive. College went from affordable to crippling.

The labor model shifted. A second income became mandatory to maintain the standard of living that one income formerly provided. But a second income meant childcare became mandatory, which meant, for many, two cars became mandatory. The composition of household spending transformed completely.

This is a very common sentiment and one of the main ways that people prone to a declinist narrative about standards of living present their case. Yglesias responds to it by saying that Green and those like him are simply wrong on the facts. If you look at the way single-earner families in the 1960s actually lived — their actual housing, their actual cars, their actual food consumption, and so on — and add it up, a single-earner family could still live like that today. It’s just that most people these days consider such a lifestyle to be a bad standard of living.

I don’t think there is any way to salvage Green’s actual argument. It’s too much of a mess. But given that so many people of all political stripes talk so much about the mid-century and specifically single-earner married families in the mid-century, there may be some value in trying to tease out an argument that these commentators perhaps feel but can’t really articulate. And I think I know what that argument is.

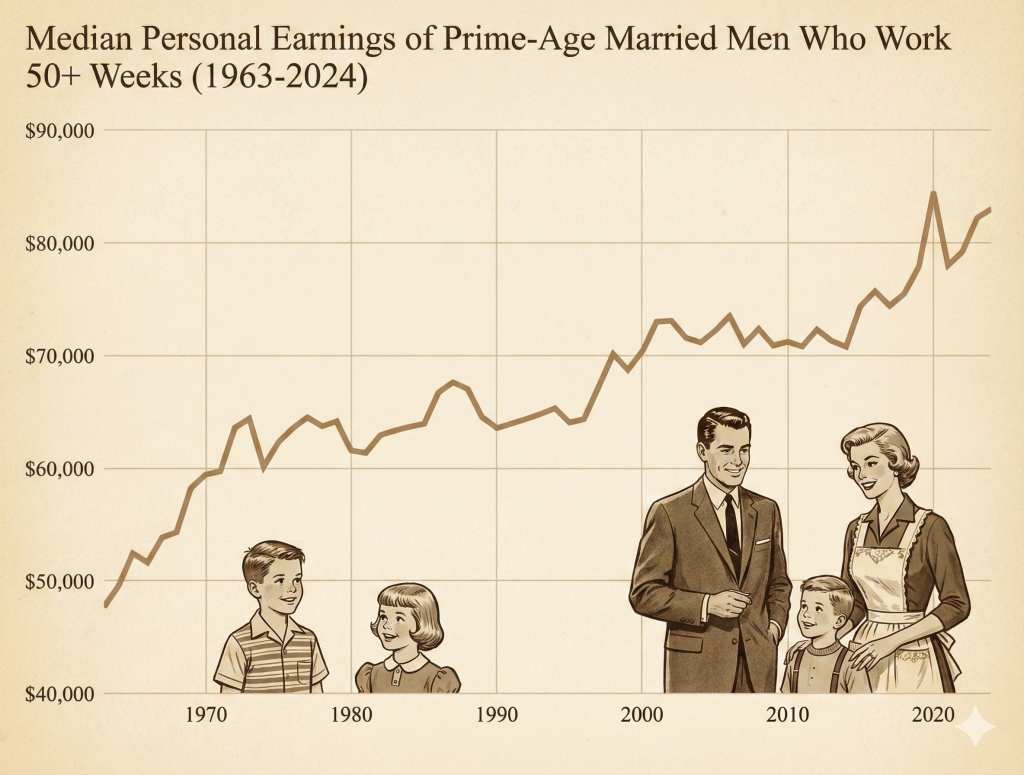

Using the Current Population Survey, I calculated the median personal earnings of married men between the ages of 25 and 54 who worked 50 or more weeks per year between 1963 and 2024. I converted the figures into 2024 dollars using the PCE inflation index.

In 1963, the median man so defined earned $47,707. In 2024, he earned $83,000. One can quibble with the inflation adjustment in various ways, but it is going to be very difficult to quibble with it enough to make the 2024 figure lower than the 1963 figure. Thus, a single-earner family headed by this sort of man should be able to have a standard of living that is at least equal to their 1963 predecessor.

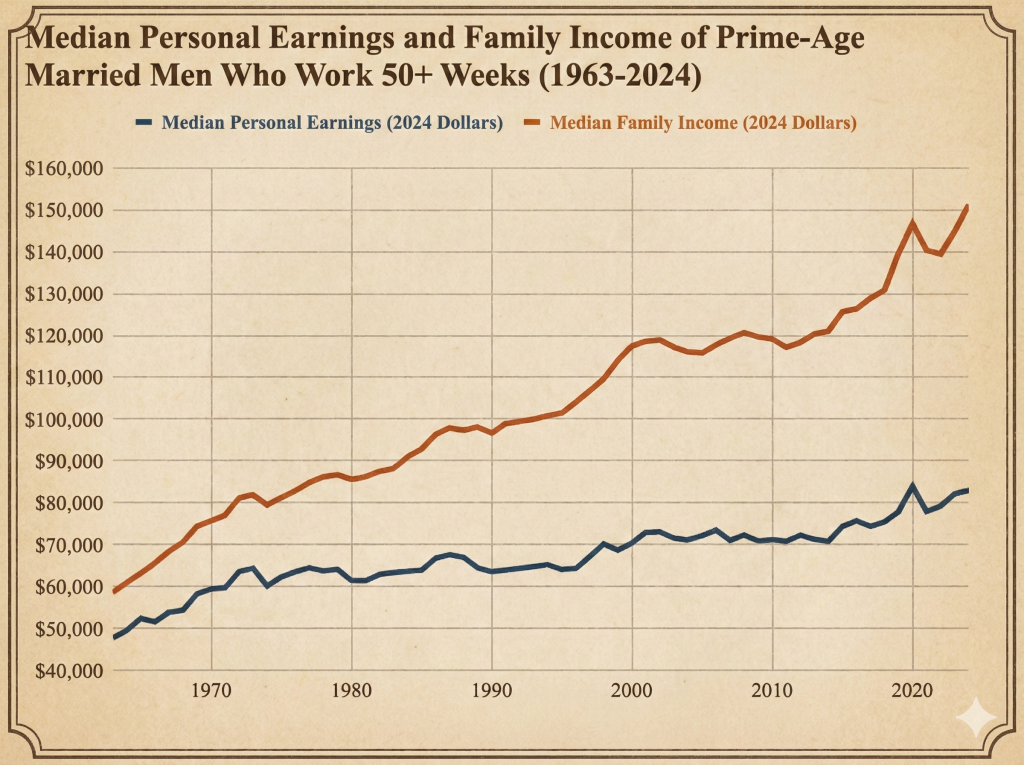

I also calculated the median family income of these same men over this period. The below graph includes these numbers as a second line.

In 1963, these men had a total family income of $58,668. In 2024, it was $151,150, a number that reflects both the rise in the married men’s earnings and the rise in their spouse’s earnings. Dual-earning families have some extra expenses like child care and multiple cars, but across the entire lifecycle (not just the years when they have two kids below school age), dual-earner families wind up way ahead.

This all raises an obvious question: if the median married man who works full time is personally earning more than his 1960s predecessor and his family is receiving way more income than before, why do people feel like they are falling behind and why is this expressed so often by talking about how you used to be able to live well on a single income but now you can’t? I think the answer can be found by dividing these two numbers.

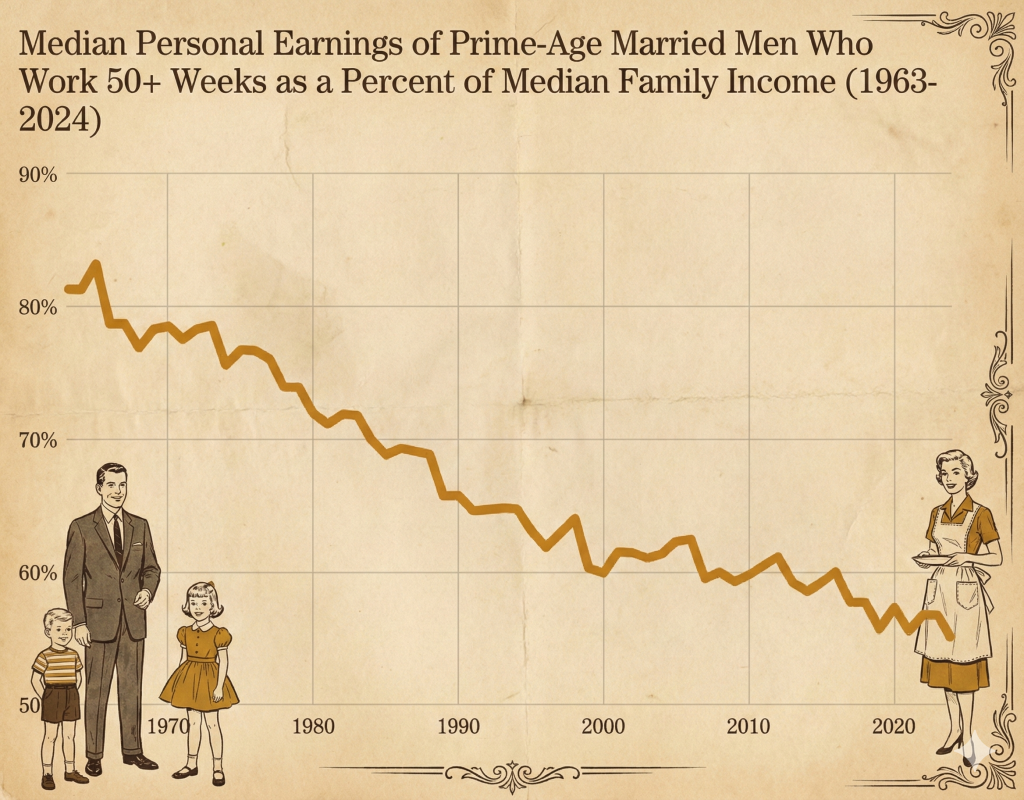

In the graph below, I have plotted the median personal earnings of these men as a share of the median family income of these men. What this graph shows is how much distance there would be between a family with a sole male breadwinner who earned the median wage and the actual median family income.

In 1963, a family surviving solely off a median married man’s wage would have an income that was 81 percent of the median family income. In 2024, such a family would have an income that is just 55 percent of the median family income. So hypothetical sole-breadwinner families went from being just a little bit poorer than the “typical” American family to being way poorer than that family. This is not because their income fell. It’s because dual-earning pushed up the median so much.

With these figures, we can see that there is no contradiction between the following three claims:

- Married men earn more than ever.

- Their families have more income than ever.

- A typical median married man used to earn enough money to be able to support a mainstream (i.e. close to the median) standard of living by himself. Now he cannot.

Nobody really presents the issue this way for obvious reasons: it’s not nearly as compelling or sympathetic as an argument that “real” median living standards are falling under this or that boutique definition of the term. People also just struggle in general to convert their intuitions and feelings about the state of things into concrete theories that are consistent with the facts and often wind up grasping at straws that are “directionally right” but “actually wrong.”

If we can agree that this is basically what people are talking about when making Green-style arguments, then we can begin the conversation about whether (3) is a problem and, if so, what exactly to do about it. Here are some possible approaches:

- Reject the idea that it is a problem. If a family wants to put in half as many work hours as another family, then they will have to survive on half as much income. This is true for families that opt for single-earning rather than dual-earning just as it is true for someone who chooses to work 20 hours per week instead of 40 hours per week.

- Accept the idea that it is a problem and try to solve it by somehow forcing more dual-earner families to become single-earner families, thereby mechanically reducing median family income and bringing the incomes of single-earner families closer to the median. This is essentially what many social conservatives want, though they are often sheepish about actually saying it (except for maybe Scott Yenor).

- Accept the idea that it is a problem and try to solve it by compressing the income differences between dual-earner and single-earner families. The straightforward way of doing this is to create universal welfare programs for children, e.g. universal health care, education, school meals, and a monthly cash benefit. These programs reduce the amount of money families need to spend out of pocket on their children while the taxes used to fund them reduce the income of dual-earner families more than sole-earner families, bringing the two closer together.

There are a lot of things you can say about the ways in which increased female labor force participation over the last half century has had big impacts on American life. Women’s economic security became less dependent on men, which shifted the balance of power between the sexes. Career development altered the timing and amount of fertility. Assortative mating based on earnings (high-earners marrying other high-earners) pushed up inequality. And it has become much harder to live a mainstream life on a single income than it once was.

But one thing you cannot say is that this shift has reduced the average material standard of living in the country. It may feel that way because the declining ability of single-earners to afford a mainstream lifestyle seems to imply that material conditions are worsening. But, as demonstrated above, there is no necessary or actual connection between these two things. Those upset about this development should confront that reality head-on rather than relying on flawed arguments to demonstrate otherwise.